The Cilium Chronicle: Remarkable Network Stability Enhancement Achieved Through Minor Code Modification

Introduction

A short while ago, I encountered a PR for the Cilium project from a former colleague.

bpf:nat: Restore ORG NAT entry if it's not found

The extent of the modification itself (excluding test code) is minimal, involving merely the addition of a single if statement block. However, the impact of this modification is substantial, and the fact that a simple idea can contribute significantly to system stability is personally intriguing. Therefore, I intend to elaborate on this case in a manner accessible even to individuals without specialized knowledge in networking.

Background Knowledge

If there is an essential item for modern individuals as important as a smartphone, it is likely the Wi-Fi router. A Wi-Fi router communicates with devices via the Wi-Fi communication standard and shares its public IP address for use by multiple devices. A technical peculiarity arises here: how exactly does it "share"?

The technology employed here is Network Address Translation (NAT). NAT is a technique that enables external communication by mapping internal communications, which consist of private IP:Port combinations, to unused public IP:Port combinations, given that TCP or UDP communication is structured as a combination of IP address and port information.

NAT

When an internal device attempts to access the external internet, a NAT device translates the device's private IP address and port number combination into its own public IP address and an arbitrarily assigned, unused port number. This translation information is recorded in a NAT table within the NAT device.

For instance, consider a scenario where a smartphone within a home (private IP: a.a.a.a, port: 50000) attempts to access a web server (public IP: c.c.c.c, port: 80).

1Smartphone (a.a.a.a:50000) ==> Router (b.b.b.b) ==> Web Server (c.c.c.c:80)

Upon receiving the smartphone's request, the router will observe the following TCP packet:

1# TCP packet received by the router, Smartphone => Router

2| src ip | src port | dst ip | dst port |

3-------------------------------------------

4| a.a.a.a | 50000 | c.c.c.c | 80 |

If this packet were forwarded directly to the web server (c.c.c.c), the response would not return to the smartphone (a.a.a.a), which has a private IP address. Therefore, the router first identifies an arbitrary port not currently involved in communication (e.g., 60000) and records it in its internal NAT table.

1# Router's internal NAT table

2| local ip | local port | global ip | global port |

3-----------------------------------------------------

4| a.a.a.a | 50000 | b.b.b.b | 60000 |

After recording the new entry in the NAT table, the router modifies the source IP address and port number of the TCP packet received from the smartphone to its own public IP address (b.b.b.b) and the newly allocated port number (60000), then transmits it to the web server.

1# TCP packet sent by the router, Router => Web Server

2# SNAT performed

3| src ip | src port | dst ip | dst port |

4-------------------------------------------

5| b.b.b.b | 60000 | c.c.c.c | 80 |

Now, the web server (c.c.c.c) recognizes the request as originating from port 60000 of the router (b.b.b.b) and sends the response packet back to the router as follows:

1# TCP packet received by the router, Web Server => Router

2| src ip | src port | dst ip | dst port |

3-------------------------------------------

4| c.c.c.c | 80 | b.b.b.b | 60000 |

Upon receiving this response packet, the router consults its NAT table to find the original private IP address (a.a.a.a) and port number (50000) corresponding to the destination IP address (b.b.b.b) and port number (60000), and then changes the packet's destination to the smartphone.

1# TCP packet sent by the router, Router => Smartphone

2# DNAT performed

3| src ip | src port | dst ip | dst port |

4-------------------------------------------

5| c.c.c.c | 80 | a.a.a.a | 50000 |

Through this process, the smartphone perceives itself as communicating directly with the web server using its own public IP address. Thanks to NAT, multiple internal devices can simultaneously access the internet using a single public IP address.

Kubernetes

Kubernetes possesses one of the most sophisticated and intricate network structures among recently developed technologies. Furthermore, the aforementioned NAT is utilized in various contexts. The following two cases are representative examples.

When a Pod performs communication with the external cluster from within the Pod

Pods within a Kubernetes cluster are typically assigned private IP addresses that allow communication only within the cluster network. Therefore, if a Pod needs to communicate with the external internet, NAT is required for outbound traffic. In this scenario, NAT is primarily performed on the Kubernetes node (each server in the cluster) where the Pod is running. When a Pod sends a packet destined for external communication, the packet is first delivered to the node to which the Pod belongs. The node then translates the source IP address of this packet (the Pod's private IP) to its own public IP address and appropriately modifies the source port before forwarding it externally. This process is analogous to the NAT process described earlier for Wi-Fi routers.

For example, assuming a Pod (10.0.1.10, port: 40000) within a Kubernetes cluster attempts to access an external API server (203.0.113.45, port: 443), the Kubernetes node will receive the following packet from the Pod:

1# TCP packet received by the node, Pod => Node

2| src ip | src port | dst ip | dst port |

3---------------------------------------------------

4| 10.0.1.10 | 40000 | 203.0.113.45 | 443 |

The node then records the following information:

1# Node's internal NAT table (example)

2| local ip | local port | global ip | global port |

3---------------------------------------------------------

4| 10.0.1.10 | 40000 | 192.168.1.5 | 50000 |

Subsequently, it performs SNAT and sends the packet externally as follows:

1# TCP packet sent by the node, Node => API Server

2# SNAT performed

3| src ip | src port | dst ip | dst port |

4-----------------------------------------------------

5| 192.168.1.5 | 50000 | 203.0.113.45 | 443 |

The subsequent process mirrors the smartphone and router scenario described earlier.

When communicating with a Pod from outside the cluster via NodePort

One method for exposing services externally in Kubernetes is to use NodePort services. A NodePort service opens a specific port (NodePort) on all nodes within the cluster and forwards traffic arriving at this port to the Pods belonging to the service. External users can access the service via the IP address of a cluster node and the NodePort.

In this context, NAT plays a crucial role, specifically involving DNAT (Destination NAT) and SNAT (Source NAT) occurring simultaneously. When traffic arrives at a specific node's NodePort from an external source, the Kubernetes network must ultimately forward this traffic to the Pod providing the service. In this process, DNAT first occurs, changing the packet's destination IP address and port number to the Pod's IP address and port number.

For example, suppose an external user (203.0.113.10, port: 30000) accesses a service through NodePort (30001) of a Kubernetes cluster node (192.168.1.5). This service internally points to a Pod with IP address 10.0.2.15 and port 8080.

1External User (203.0.113.10:30000) ==> Kubernetes Node (External:192.168.1.5:30001 / Internal: 10.0.1.1:42132) ==> Kubernetes Pod (10.0.2.15:8080)

Here, the Kubernetes node possesses both the externally accessible node IP address 192.168.1.5 and the internally valid Kubernetes network IP address 10.0.1.1. (Policies related to this vary depending on the CNI type used, but this article explains it based on Cilium.)

When an external user's request arrives at the node, the node must forward this request to the Pod that will handle it. At this point, the node applies the following DNAT rule to change the packet's destination IP address and port number:

1# TCP packet being prepared by the node for transmission to the Pod

2# After DNAT application

3| src ip | src port | dst ip | dst port |

4---------------------------------------------------

5| 203.0.113.10 | 30000 | 10.0.2.15 | 8080 |

A critical point here is that when the Pod sends a response to this request, its source IP address will be its own IP address (10.0.2.15), and the destination IP address will be that of the external user who initiated the request (203.0.113.10). In such a scenario, the external user would receive a response from a non-existent IP address that they never requested and would simply DROP the packet. Therefore, the Kubernetes node additionally performs SNAT when the Pod sends a response packet externally, changing the packet's source IP address to the node's IP address (192.168.1.5 or the internal network IP 10.0.1.1, in this case, 10.0.1.1).

1# TCP packet being prepared by the node for transmission to the Pod

2# After DNAT, SNAT application

3| src ip | src port | dst ip | dst port |

4---------------------------------------------------

5| 10.0.1.1 | 40021 | 10.0.2.15 | 8080 |

Now, the Pod that received this packet will respond to the node that originally received the NodePort request, and the node will reverse the same DNAT and SNAT processes to return the information to the external user. During this process, each node will store information similar to the following:

1# Node's internal DNAT table

2| original ip | original port | destination ip | destination port |

3------------------------------------------------------------------------

4| 192.168.1.5 | 30001 | 10.0.2.15 | 8080 |

5

6# Node's internal SNAT table

7| original ip | original port | destination ip | destination port |

8------------------------------------------------------------------------

9| 203.0.113.10 | 30000 | 10.0.1.1 | 42132 |

Main Discussion

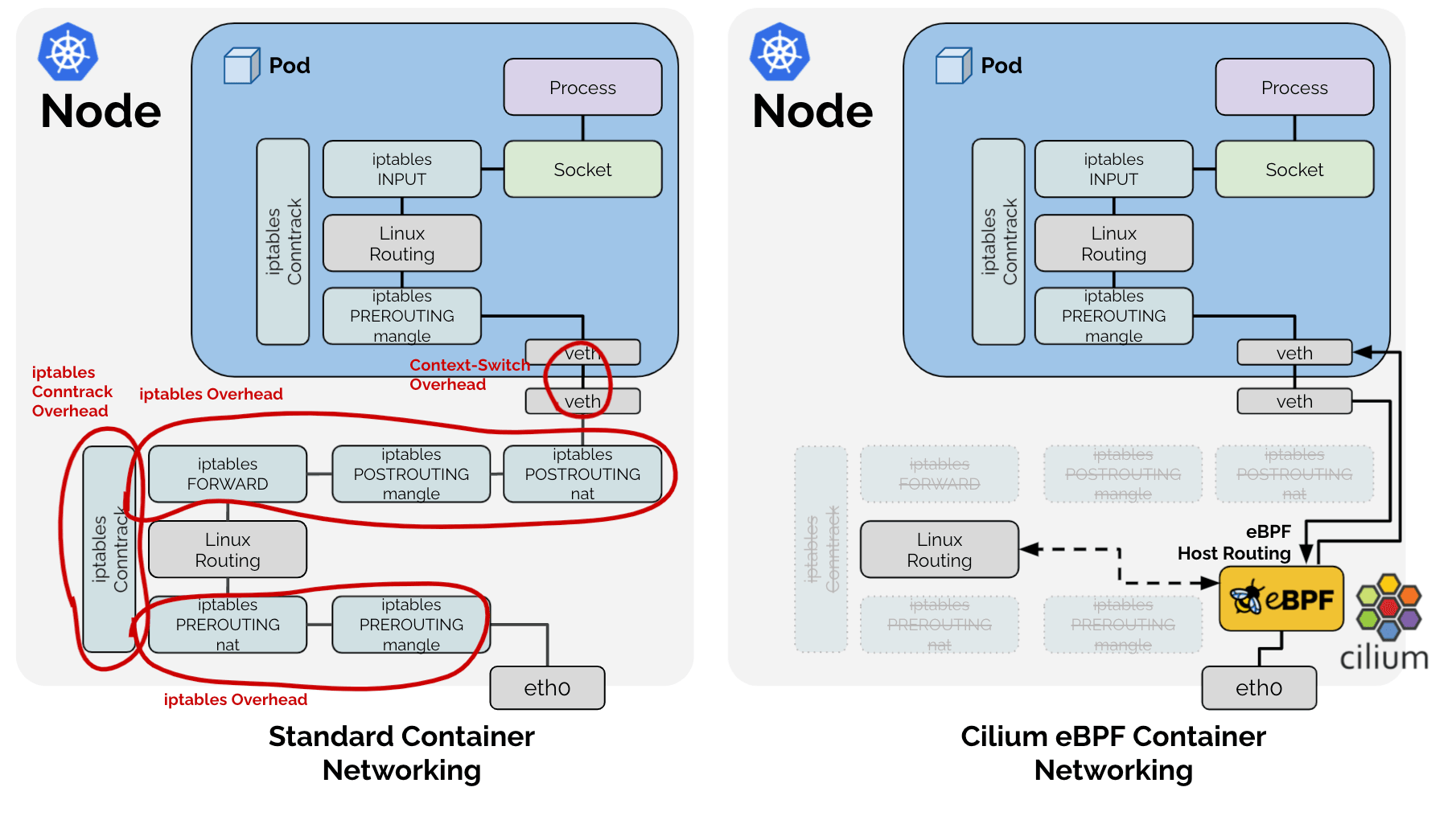

Typically, in Linux, these NAT processes are managed and operated by the conntrack subsystem via iptables. In fact, other CNI projects such as flannel and calico leverage this to address the aforementioned issues. However, the problem arises because Cilium, by utilizing eBPF technology, completely bypasses this traditional Linux network stack. 🤣

As a result, Cilium opted to directly implement only the functionalities required in a Kubernetes context from the tasks previously handled by the traditional Linux network stack, as shown in the figure above. Therefore, for the aforementioned SNAT process, Cilium directly manages the SNAT table in the form of an LRU Hash Map (BPF_MAP_TYPE_LRU_HASH).

1# Cilium SNAT table

2# !Example for easy explanation. Actual definition: https://github.com/cilium/cilium/blob/v1.18.0-pre.1/bpf/lib/nat.h#L149-L166

3| src ip | src port | dst ip | dst port | protocol, conntrack, and other metadata

4----------------------------------------------

5| | | | |

And as it is a Hash Table, for fast lookups, a key value exists, using a combination of src ip, src port, dst ip, dst port as the key.

Problem Identification

Phenomenon - 1: Lookup

Consequently, one problem arises: to verify whether a packet passing through eBPF requires SNAT or DNAT for the NAT process, the aforementioned Hash Table must be queried. As previously observed, two types of packets exist in the SNAT process: 1. packets originating from inside and moving outside, and 2. response packets returning from outside to inside. These two packets require NAT transformation and are characterized by swapped src ip, port, and dst ip, port values.

Therefore, for rapid lookup, either an additional value with swapped src and dst as the key could be added to the Hash Table, or the same Hash Table would need to be queried twice for all packets, even those unrelated to SNAT. Naturally, Cilium adopted the method of inserting the same data twice, under the name RevSNAT, for improved performance.

Phenomenon - 2: LRU

Furthermore, separate from the above issue, infinite resources cannot exist on any hardware, and particularly in hardware-level logic where high performance is required and dynamic data structures cannot be employed, existing data must be evicted when resources are scarce. Cilium addresses this by utilizing the LRU Hash Map, a basic data structure provided by Linux.

Phenomenon 1 + Phenomenon 2 = Connection Loss

https://github.com/cilium/cilium/issues/31643

Specifically, for a single SNATed TCP (or UDP) connection:

- The same data is recorded twice in a single Hash Table for outgoing and incoming packets.

- Due to LRU logic, either of these data entries can be lost at any time.

If even one NAT entry (hereinafter referred to as entry) for an outgoing or incoming packet is lost due to LRU, NAT cannot be performed correctly, potentially leading to the loss of the entire connection.

Solution

This is where the previously mentioned PRs come into play:

bpf:nat: restore a NAT entry if its REV NAT is not found

bpf:nat: Restore ORG NAT entry if it's not found

Previously, when a packet traversed eBPF, it attempted a lookup in the SNAT table using a key composed of src ip, src port, dst ip, and dst port. If the key did not exist, new NAT information was generated according to SNAT rules and recorded in the table. For a new connection, this would lead to normal communication. However, if the key was unintentionally removed by LRU, a new NAT would be performed using a port different from the one used for the existing communication, causing the receiving end to reject the packet, and the connection would terminate with an RST packet.

The approach taken by the aforementioned PR is straightforward:

If a packet is observed in one direction, the entry for the reverse direction should also be updated.

When communication is observed in either direction, both entries are updated, moving them away from being priorities for LRU eviction. This reduces the possibility of a scenario where the entire communication collapses due to the deletion of only one entry.

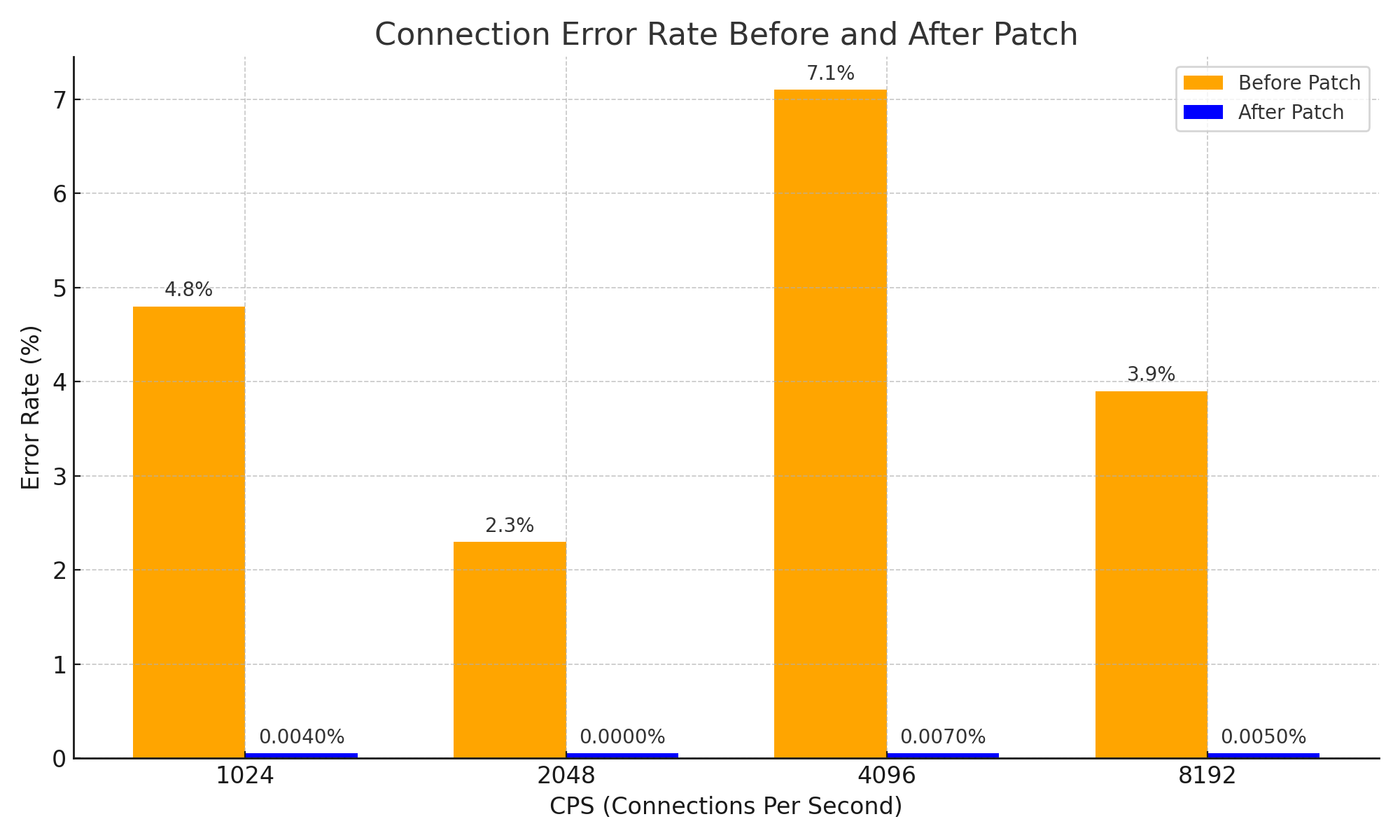

While this may seem like a very simple approach and a basic idea, it has effectively resolved the issue of connection drops caused by the premature expiration of NAT information for response packets, significantly enhancing system stability. It also represents a crucial improvement in terms of network stability, achieving the following results:

Conclusion

I consider this PR an excellent example that demonstrates how a simple idea, starting from fundamental CS knowledge of how NAT operates, can bring about significant changes even within complex systems.

Of course, I did not directly present a case of a complex system in this article. However, to properly comprehend this PR, I pleaded with DeepSeek V3 0324 for nearly 3 hours, even adding the word "Please," and as a result, gained +1 knowledge about Cilium and obtained the following diagram. 😇

And after reading through the issues and PRs, I am writing this article as a form of compensatory psychology for the ominous premonitions that issues might have arisen due to something I created in the past.

Postscript - 1

Incidentally, there is a very effective way to avoid this issue. Since the root cause of the issue is insufficient NAT table space, increasing the size of the NAT table resolves it. :-D

While someone else might have encountered the same issue, increased the NAT table size, and then disappeared without even logging an issue, I was impressed and respected by the passion of gyutaeb for thoroughly analyzing, understanding, and contributing to the Cilium ecosystem with objective supporting data, even though the issue was not directly related to him.

This was the motivation for deciding to write this article.

Postscript - 2

This topic is not directly aligned with Gosuda, which specializes in the Go language. However, given the close relationship between the Go language and the cloud ecosystem, and the fact that Cilium contributors generally possess some proficiency in Go, I decided to bring content that could have been posted on a personal blog to Gosuda.

Since one of the administrators (myself) granted permission, I presume it will be acceptable.

If you believe it is not acceptable, you might want to save it as a PDF quickly, as its deletion date is uncertain. ;)

Postscript - 3

This article greatly benefited from the assistance of Cline and Llama 4 Maveric. Although I began my analysis with Gemini and pleaded with DeepSeek, it was ultimately Llama 4 that provided significant help. Llama 4 is excellent; I highly recommend trying it.